COVID vaccines train your immune system to fight off COVID-19. Most work by giving your body a set of instructions (mRNA) to make a harmless piece of the virus for your immune system to recognize. Others work by causing an immune reaction to COVID’s spike protein. You might have some side effects like a sore arm, muscle aches or fatigue.

COVID vaccines are preventive treatments that train your body to recognize and quickly fight a COVID-19 infection. This means if you’re exposed to COVID, you might not get sick or you’ll get less severely sick than you would have without vaccination.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and World Health Organization (WHO) authorized the first COVID vaccines for emergency use in 2020. They were effective against the original strain of COVID. Since then, SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID, has changed (mutated). New variants, like many Omicron subvariants, are different enough from the original strain that the first vaccines aren’t as effective against it. Some manufacturers have created updated vaccines that train your immune system to recognize new variants and continue to provide protection.

While many people call them “boosters,” the most recent COVID shots aren’t boosters. They’re vaccines that have been updated to target the most common variant. This is similar to how the flu shot is updated every year.

Boosters are additional doses of the same vaccine needed to maintain immunity if it decreases over time. Updated vaccines protect against new versions of a virus.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

In the U.S., recommendations change frequently and depend on your age, previous vaccinations and the manufacturer of the vaccine. Adults and children 5 years and older with healthy immune systems should get one dose of an updated COVID-19 shot to be considered up to date. Kids ages 6 months to 4 years old need multiple doses to be up to date, and at least one of these doses should be the updated COVID-19 shot.

If you have a compromised immune system, you might need additional doses to be protected. Always double-check with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) or ask your healthcare provider for current recommendations.

Experts aren’t yet sure whether we’ll need new COVID vaccines yearly, similarly to flu shots. In the U.S., the FDA and CDC currently recommend that manufacturers update their vaccines if they’re needed to protect against new variants.

COVID vaccines, like all vaccines, work by training your immune system to fight off harmful germs (pathogens) that attempt to invade your body. But what does that mean? First, we have to understand how your immune system fights off viruses, bacteria and other pathogens.

Each pathogen has a unique part that your body recognizes as an invader, called an antigen. It’s like a distinctive birthmark or tattoo you look for to identify someone. In COVID-19, it’s a protein that sticks out all around the outside of the virus (the spike protein).

The first time an invader, like a virus or bacteria, enters your body, your immune system needs to look for the right tools (specific B-cells) to recognize the antigen and destroy the pathogen it belongs to. When your immune cells find the right tools, they make a lot of them to find and get rid of the infection. But this process can take some time.

You also have special cells that remember the pathogen (memory B-cells). Like taking a photo and putting it on a “wanted” poster, your immune cells can then patrol your body, looking for familiar pathogens. If they encounter one, they can destroy it much more quickly than the first time it infected you — often before it makes you sick at all. This is called adaptive immunity.

COVID vaccines aim to tell your body what SARS-CoV-2 looks like without actually getting an infection. Then your immune system can build up its tools and surveillance team, so when it sees the virus, it can fight it off quickly. For some people, this means they don’t get sick at all if they’re exposed to COVID. Other times, it makes their symptoms less severe and allows them to recover more quickly.

Advertisement

There are currently three updated COVID-19 vaccines available in the U.S. They’re categorized based on the method they use to get your body to recognize the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2.

Viral vector vaccines (Johnson & Johnson/Janssen®) are no longer available in the U.S. These used a different, harmless virus and a small part of COVID’s genetic code (DNA) to train your immune system.

mRNA vaccines don’t use a part of the virus to train your immune system. Instead, they give your body instructions that it uses to manufacture harmless proteins that look like parts of the virus (in the case of COVID, the spike protein). Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines are mRNA vaccines. Your body uses the mRNA instructions to make the spike protein for your immune system to recognize.

Protein subunit vaccines use a part of the virus to get an immune system response. The Novavax vaccine delivers the spike protein to your cells so they can recognize and be prepared to destroy it if they see it again. Since it’s just part of the virus and not the actual virus itself, it can’t make more copies of itself or hurt you.

Before getting your COVID shot, you should:

Advertisement

Healthcare providers give all COVID vaccines as injections (shots). In adults and children over 5, a provider gives you the injection into the muscle of your upper arm. In children under 5, the injection is in their thigh (though 3- and 4-year-olds sometimes get it in their arms).

A provider will clean the area with an alcohol swab and inject the vaccine with a needle. They’ll put a bandage over it. Sometimes they’ll put a small, round bandage (a pre-injection bandage, or an Inject-Safe™ barrier bandage) on first and inject the needle into your skin through the bandage.

Your provider may ask you to wait at least 15 minutes before leaving to make sure you don’t have an immediate allergic reaction.

Studies suggest COVID vaccines are most effective in the first few months following your shot. That’s why when health experts recommend boosters or updated doses, they’re usually given three to four months after your last COVID shot.

Studies suggest that people who are vaccinated against COVID-19 are less likely than those who aren’t vaccinated to:

Moderna, Pfizer-BioNTech and Novavax vaccines have all been tested and proven safe. Like every medicine, COVID vaccines go through a series of tests to learn whether they’re safe and effective (clinical trials). Thousands of volunteers receive a vaccine before it’s approved for the public. Vaccine manufacturers didn’t skip any of these tests before the FDA and other public health organizations around the world approved their COVID vaccines.

A medication that uses the same RNA technology had been tested and approved before COVID vaccines were developed. This made COVID vaccine development faster than vaccines before it.

No matter which type of shot you get, your body breaks down the ingredients or they’re destroyed by your immune system within a few days. This means vaccines can’t cause long-lasting health effects.

All that being said, any vaccine or medication has a risk of side effects and allergic reactions, which can sometimes be severe. Serious health conditions as a result of COVID vaccination are very rare.

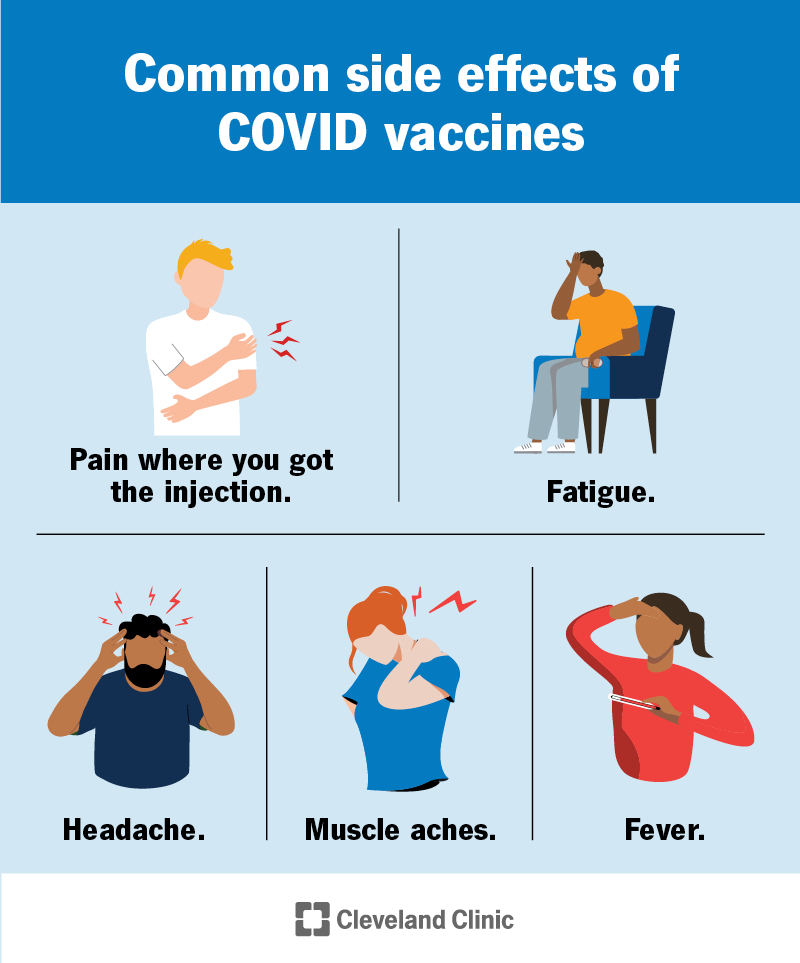

The most common risk of getting a COVID vaccine is experiencing unpleasant but harmless side effects. Side effects of the COVID vaccine include:

Side effects like muscle aches, tiredness and fever usually last a day or two. Your arm might hurt for several days.

Serious complications of COVID vaccines are rare. They include:

Some people have an allergic reaction to the ingredients in vaccines. About 1 in 200,000 people who get a COVID shot have anaphylaxis. Anaphylaxis is a life-threatening reaction that causes swelling and extremely low blood pressure. The risk of severe allergic reactions is the reason your provider asks you to wait for 15 minutes after getting your shot — so you can get medical attention right away if you experience an unexpected reaction.

Symptoms of an allergic reaction include:

Some people have had an inflammation of their heart muscle (myocarditis) or the outer lining of their heart (pericarditis) after getting an mRNA vaccine. Though rare, it’s most common in men and people assigned male at birth (AMAB) between the ages of 18 and 29 after getting their second shots.

Symptoms of pericarditis and myocarditis include:

You shouldn’t get a COVID vaccine if you:

If you get your shot while you’re sick with COVID, you could end up making yourself feel sicker. You also risk getting other people sick with COVID by going out to get vaccinated.

It’s not necessary to get a COVID vaccine if you’ve recently been sick — it won’t help you get better faster, and you’ll get natural immunity from your body fighting it off. COVID immunity lasts several months after an infection, but can decrease over time. If you’re not up to date on your vaccines, you could consider waiting three months after your symptoms started or you tested positive to get vaccinated.

Go to an emergency room immediately if you have signs of a severe allergic reaction, including trouble breathing, severe hives or swelling of your face, lip, tongue or throat.

Talk to your healthcare provider if you:

The FDA authorized the first COVID vaccines for emergency use in the U.S. in December of 2020. It might seem like they came out fast. But decades of research went into developing the technology that now makes vaccines faster and easier to develop.

Research into mRNA technology dates back to the 1970s. Scientists first started applying it to vaccine development in the 1990s. It took over 20 years of research to learn how to get our immune systems to recognize the mRNA without destroying it too quickly, and how to get it into our cells.

Finally, in 2018, the FDA approved patisiran (Onpattro®), a drug that treats a rare nerve disease. The method patisiran uses to deliver RNA (lipid nanoparticles) paved the way for Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech to use it in their COVID vaccines.

Anyone living in the U.S. can get their COVID vaccine for free. Insurance is required to cover it (check with your insurer for covered locations). If you don’t have insurance, COVID vaccines are still free through the Bridge Access Program through the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

Thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome (TTS), a condition that can cause blood clots, was an extremely rare complication of certain COVID vaccines that are no longer available. The condition activates your platelets, part of your blood that helps it clot.

About 1 in 250,000 people had TTS after getting Johnson & Johnson/Janssen or AstraZeneca® vaccines. Johnson & Johnson/Janssen and AstraZeneca COVID vaccines are no longer available, and AstraZeneca vaccines were never used in the U.S. Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines aren’t associated with TTS.

A note from Cleveland Clinic

Scientists were able to develop COVID vaccines in record time thanks to decades of research in mRNA technology. Before the vaccines, millions of people were seriously ill or died of COVID-19. Hospitals were overflowing. Since the FDA authorized the first COVID vaccines in late 2020, over 270 million people (or 81% of the U.S. population) have received at least one dose. This has prevented millions of deaths and hospitalizations. The technology they use is promising for developing future vaccines quickly.

Last reviewed on 10/23/2023.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy