Alzheimer’s disease causes a decline in memory, thinking, learning and organizing skills over time. It’s the most common cause of dementia and usually affects people over the age of 65. There’s no cure for Alzheimer’s, but certain medications and therapies can help manage symptoms temporarily.

Alzheimer’s disease (pronounced “alz-HAI-mirs”) is a brain condition that causes a progressive decline in memory, thinking, learning and organizing skills. It eventually affects a person’s ability to carry out basic daily activities. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia.

The symptoms of Alzheimer’s worsen over time. Researchers believe the disease process may start 10 years or more before the first symptoms appear. AD most commonly affects people over the age of 65.

Dementia describes the state of a person’s mental function. It’s not a specific disease. It’s a decline in mental function from a previously higher level that’s severe enough to interfere with daily living.

A person with dementia has two or more of these specific difficulties, including a change or decline in:

Dementia ranges in severity. In the mildest stage, you may notice a slight decline in your mental functioning and require some assistance on daily tasks. At the most severe stage, a person depends completely on others for help with simple daily tasks.

Dementia develops when infections or diseases impact the parts of your brain involved with learning, memory, decision-making or language. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia, accounting for at least two-thirds of dementia cases in people 65 and older.

Other common causes of dementia include:

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Alzheimer’s disease mainly affects people over age 65. The higher your age over 65, the more likely you’ll develop Alzheimer’s.

Some people develop Alzheimer’s disease before age 65 — typically in their 40s or 50s. This is called early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. It’s rare. Less than 10% of AD cases are early-onset.

Alzheimer’s disease is common. It affects approximately 24 million people across the world. One in 10 people older than 65 and nearly a third of people older than 85 have the condition.

Advertisement

Alzheimer’s disease organizations and healthcare providers use various terms to describe the stages of Alzheimer’s disease based on symptoms.

While the terms vary, the stages all follow the same pattern — AD symptoms progressively worsen over time.

No two people experience AD in the same way, though. Each person with Alzheimer’s disease will progress through the stages at different speeds. Not all changes will occur in each person. It can sometimes be difficult for providers to place a person with AD in a specific stage as stages may overlap.

Some organizations and providers frame the stages of Alzheimer’s disease in terms of dementia:

Other organizations and providers more broadly explain the stages as:

Or:

Don’t be afraid to ask your healthcare provider or your loved one’s provider what they mean when they use certain words to describe the stages of Alzheimer’s.

Providers typically only reference the preclinical stage in research on Alzheimer’s disease. People with AD in the preclinical stage typically have no symptoms (are asymptomatic).

However, changes are taking place in their brain. This stage can last for years or even decades. People in this stage aren’t usually diagnosed with Alzheimer’s yet because they’re functioning at a high level.

There are now brain imaging tests that can detect deposits of a protein in your brain called amyloid that interfere with your brain’s communication system before symptoms start.

When memory problems become noticeable, healthcare providers often identify it as mild cognitive impairment (MCI). It’s a slight decline in mental abilities compared with others of the same age.

You may notice a minor decline in abilities if you’re in the early stages of Alzheimer’s. Others close to you may notice these changes and point them out. But the changes aren’t severe enough to interfere with daily life and activities.

In some cases, the effects of a treatable illness or disease cause mild cognitive impairment. However, for most people with MCI, it’s a point along the pathway to dementia.

Researchers consider MCI to be the stage between the mental changes seen in normal aging and early-stage dementia. Various diseases can cause MCI, including Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease. Similarly, dementia can have a variety of causes.

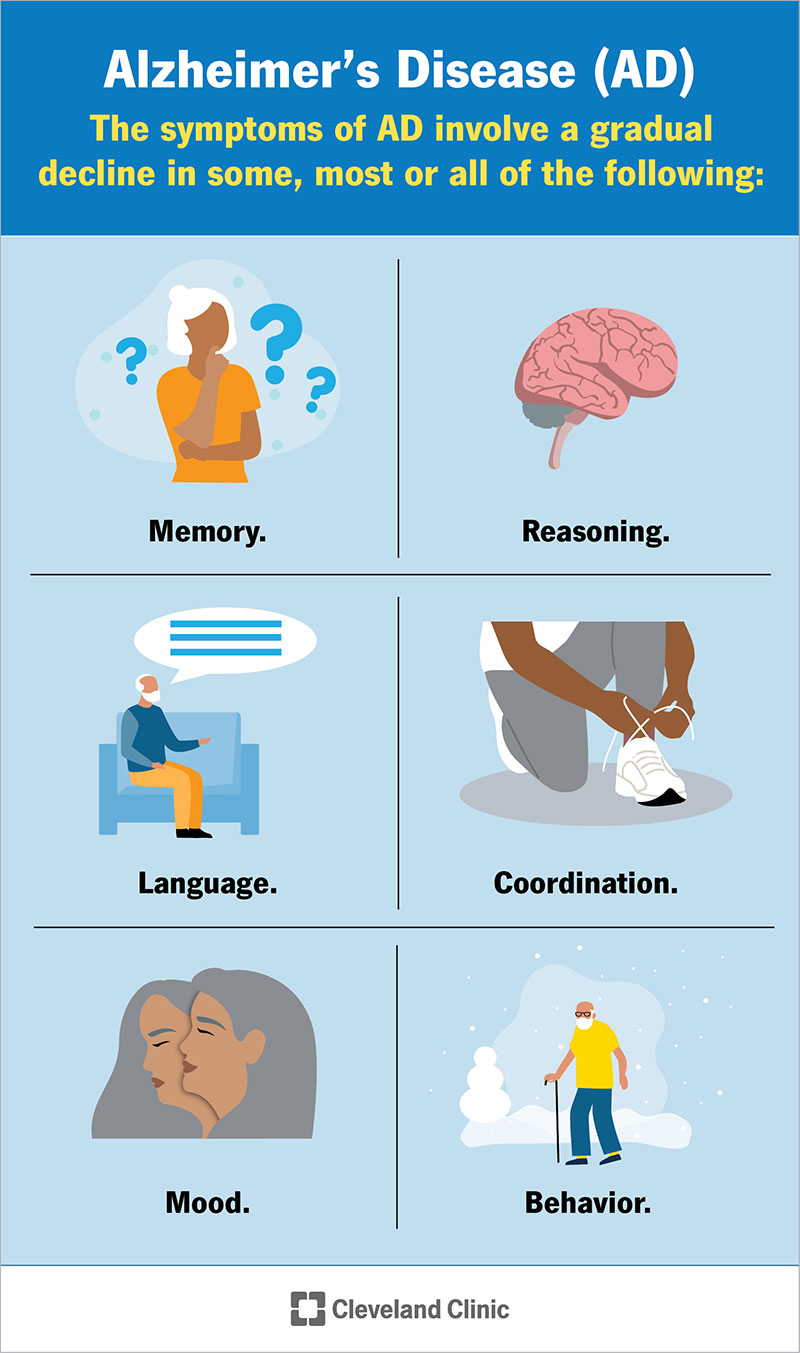

The signs and symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) vary based on the stage of the condition. In general, the symptoms of AD involve a gradual decline in some, most or all of the following:

People with memory loss or other signs of Alzheimer’s may have difficulty recognizing their mental decline. These signs may be more obvious to loved ones. Anyone experiencing dementia-like symptoms should see a healthcare provider as soon as possible.

Symptoms of AD become noticeable in the mild stage. The most common early symptom is forgetting newly learned information, especially recent events, places and names.

Other signs and symptoms of mild Alzheimer’s include:

Most people in the mild stage of AD have no problem recognizing familiar faces and can usually travel to familiar places.

Moderate Alzheimer’s is typically the longest stage and can last many years. People in the moderate stage of Alzheimer’s often require care and assistance.

People in this stage may:

In the final stage of Alzheimer’s, dementia symptoms are severe. People in this stage need extensive care.

In the severe stage of Alzheimer’s disease, the person often:

Hospice care may be appropriate at this time for comfort.

Advertisement

An abnormal build-up of proteins in your brain causes Alzheimer’s disease. The build-up of these proteins — amyloid protein and tau protein — causes brain cells to die.

The human brain contains over 100 billion nerve cells and other cells. The nerve cells work together to fulfill all the communications needed to perform functions such as thinking, learning, remembering and planning.

Scientists believe that amyloid protein builds up in your brain cells, forming larger masses called plaques. Twisted fibers of another protein called tau form into tangles. These plaques and tangles block the communication between nerve cells, which prevents them from carrying out their processes.

The slow and ongoing death of the nerve cells results in the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. Nerve cell death starts in one area of your brain (usually in the area of your brain that controls memory — the hippocampus) and then spreads to other areas.

Despite ongoing research, scientists still don’t know what exactly causes these proteins to build up. So far, they believe that a genetic mutation may cause early-onset Alzheimer’s. They think that late-onset Alzheimer’s happens due to a complex series of brain changes that may occur over decades. A combination of genetic, environmental and lifestyle factors likely contribute to the cause.

Researchers don’t know why some people get Alzheimer’s disease and others don’t. But they’ve identified several factors that increase your risk for Alzheimer’s, including genetic (hereditary) factors.

Having a form of the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene increases your risk. This gene has several forms, and one of those, APOE ε4, increases your risk of developing Alzheimer’s and is also associated with an earlier age of disease onset. However, having the APOE ε4 form of the gene doesn’t guarantee that you’ll develop the condition. Some people with no APOE ε4 may also develop Alzheimer’s.

If you have a first-degree relative (biological parent or sibling) with Alzheimer’s disease, your risk of developing the condition increases by 10% to 30%. People with two or more siblings with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease are three times more likely to develop the condition than the general population.

Having trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) also increases your risk for early-onset Alzheimer’s.

Healthcare providers use several methods to determine if a person with memory issues has Alzheimer’s disease. This is because many other conditions, especially neurological conditions, can cause dementia and other symptoms of Alzheimer’s.

In the beginning steps of an Alzheimer’s diagnosis, a provider will ask questions to better understand your health and daily living. Your provider may also ask someone close to you, like a family member or caregiver, for insight into your symptoms. They’ll ask about:

A provider will also:

There’s no cure for Alzheimer’s disease, but certain medications can temporarily slow the worsening of dementia symptoms. Medications and other interventions can also help with behavioral symptoms.

Beginning treatment as early as possible for Alzheimer’s could help maintain daily functioning for a while. However, current medications won’t stop or reverse AD.

As AD affects everyone differently, treatment is highly individualized. Healthcare providers work with people with Alzheimer’s and their caregivers to determine the best treatment plan.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved two types of drugs to treat the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease:

The FDA has given accelerated approval for aducanumab (Aduhelm™), the first disease-modifying therapy for Alzheimer’s disease. The medication helps to reduce amyloid deposits in your brain.

Aducanumab is a new medication, and researchers studied its effects in people living with early Alzheimer’s disease. Because of this, it may only help people in the early stage.

The following cholinesterase inhibitors can help treat the symptoms of mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease:

These drugs work by blocking the action of acetylcholinesterase, the enzyme responsible for destroying acetylcholine. Acetylcholine is one of the chemicals that help nerve cells communicate. Researchers believe that reduced levels of acetylcholine cause some of the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease.

These drugs can improve some memory problems and reduce some behavioral symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease.

These medications don’t cure Alzheimer’s disease or stop the progression of the disease.

Memantine (Namenda®) is FDA-approved for treating moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease. It helps keep certain brain cells healthier.

Studies have shown that people with Alzheimer’s who take memantine perform better in common activities of daily living such as eating, walking, toileting, bathing and dressing.

If your loved one has been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, you can take steps to keep them comfortable in their environment and help manage behavior changes. You can:

No medication has been approved for the management of behavioral symptoms in Alzheimer’s dementia. Certain medications may help in some people, including:

These medications can cause unpleasant or potentially dangerous side effects (like dizziness, which could lead to falls), so healthcare providers typically only prescribe them for short periods when behavioral problems are severe. Or only after your loved one has tried safer non-drug therapies first.

Scientists are actively researching Alzheimer’s disease and possible treatments. Ask your provider if there are any clinical trials that could benefit you or your loved one.

An early diagnosis often provides people with more opportunities to participate in clinical trials or other research studies.

While there are some risk factors for Alzheimer’s you can’t change, like age and genetics, you may be able to manage other factors to help reduce your risk.

Risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease include:

Research shows that having a healthy lifestyle helps protect your brain from cognitive decline. The following strategies may help decrease your risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease:

Talk to your healthcare provider if you’re concerned about your risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease.

It’s important to remember that no two people with Alzheimer’s disease are affected in the same way. It’s difficult to predict how your loved one will be affected. The best way you can prepare is to talk to healthcare providers who specialize in researching and treating Alzheimer’s disease and dementia.

As the condition progresses, your loved one may benefit from a team of providers who can care for their needs.

The prognosis (outlook) for Alzheimer’s disease is generally poor. The course of the disease varies from person to person. But on average, people with AD over 65 die within four to eight years of the diagnosis. However, some people may live up to 20 years after the first symptoms appear.

Common causes of death include:

Alzheimer’s disease is the seventh leading cause of death in the United States.

Caring for someone with Alzheimer’s can have significant physical, emotional and financial costs. The following tips can help both you and your loved one:

See a healthcare provider if you or a loved one are experiencing issues with your memory or thinking. They can determine if the issues are due to Alzheimer’s or another condition.

If you or a loved one has been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, you’ll need to see your healthcare team regularly to monitor the progression of the condition and to ensure your care plan is working for you.

If your loved one has Alzheimer’s disease, it may be helpful to ask their healthcare team the following questions:

A note from Cleveland Clinic

It can be overwhelming to learn that a loved one has Alzheimer’s disease. Know that their healthcare team will help them and you through the process and provide individualized options for care. It’s important to take care of yourself as well. Consider joining support groups or creating your own support network to help you.

Last reviewed on 12/10/2022.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy