A seizure is a condition where brain cells malfunction and send electrical signals uncontrollably. That causes symptoms affecting other parts of your brain and body. Everyone can have seizures, but some people can have them more easily for various reasons. Seizures are often treatable, especially depending on the underlying cause.

A seizure is a medical condition where you have a temporary, unstoppable surge of electrical activity in your brain. When that happens, the affected brain cells uncontrollably fire signals to others around them. This kind of electrical activity overloads the affected areas of your brain.

That overload can cause a wide range of symptoms or effects. The possible symptoms include abnormal sensations, passing out and uncontrolled muscle movements. Treatment options, depending on seizure type, include medications, surgeries and special diet changes.

The term “seizure” comes from the ancient belief in multiple cultures that seizures were a sign of possession by an evil spirit or demon. But modern medicine has uncovered the truth: Everyone can have seizures, and some people can have them more easily than others.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Understanding the difference between seizures and epilepsy starts with knowing seizures fall into two main categories depending on why they happen:

Epilepsy is a brain condition that puts you at risk of having spontaneous, unprovoked seizures. Healthcare providers diagnose it when you have at least two unprovoked seizures, or you have a single unprovoked seizure and have a high risk of having at least one more in the next 10 years. Having a single unprovoked seizure increases the odds of having another. Provoked seizures aren’t enough for a provider to diagnose you with epilepsy.

Everyone can have seizures, but some people have medical conditions that make them happen more easily. Seizures are also more likely at certain ages. Children are more likely to have seizures and epilepsy, but many grow out of the condition. The risk of having a seizure or developing epilepsy also starts rising at age 50 because of conditions like stroke.

Advertisement

Seizures are uncommon but are still well-known by most people. Up to 11% of people in the U.S. will have at least one seizure during their life.

Epilepsy is much less common. Between 1% and 3% of people in the U.S. will develop epilepsy during their lifetime.

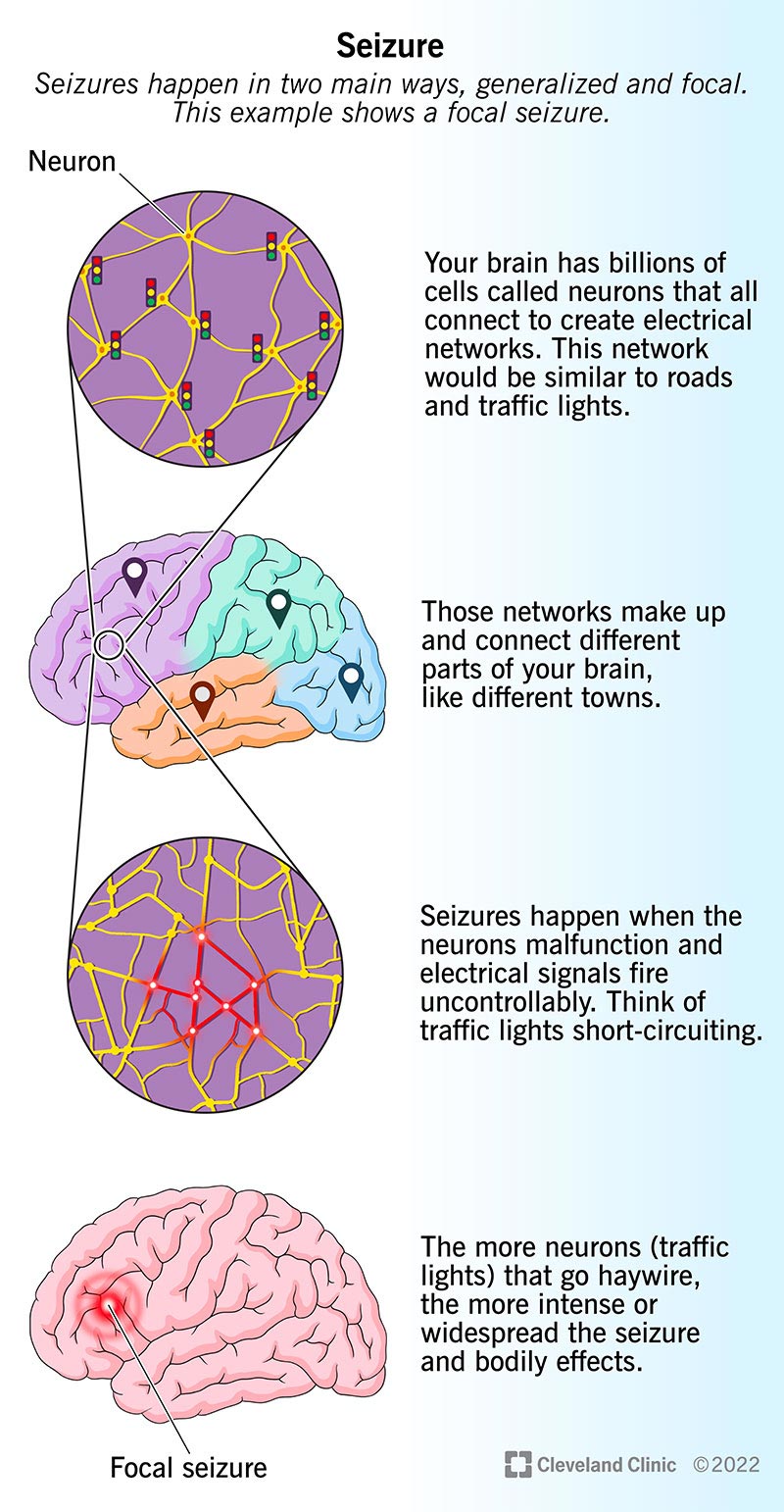

Your brain contains billions of cells known as neurons. These cells transmit and relay chemical and electrical signals to each other. A single neuron in your brain connects to thousands more, forming communicating networks. Those networks are how different parts of your brain work together so you can do things like solve problems, store memories and move around.

Seizures happen when a malfunction causes neurons to fire electrical signals uncontrollably. That causes a domino effect, meaning more and more neurons go haywire. The more malfunctioning neurons, the greater the effect of the seizure. If these malfunctions happen often enough, they can affect how your brain cells work and make it easier for seizures to happen.

If they keep happening or seizures last too long, these electrical malfunctions will damage and destroy your brain cells. When this happens to enough neurons in a part of your brain, the result could be permanent brain damage.

Seizures can also cause severe changes in your blood chemistry as your body tries to manage the physical effects of convulsions. The chemical changes in your blood can cause permanent brain damage if they last too long.

Seizure types depend partly on where they happen in your brain. A healthcare provider can determine where they happened based on your symptoms.

Seizure location tends to happen in two main ways:

Status epilepticus happens when a seizure lasts for more than five minutes, or you have more than one seizure without enough time between to recover. Status epilepticus is a life-threatening medical emergency because it can cause brain damage or even death.

Seizures often involve passing out. When that happens, there’s a risk of injuries from falling or from what you’re doing at the time (like driving or operating machinery).

Advertisement

Many people experience a period where they can feel that a seizure is going to happen. That lead-up time, known as prodrome (rhymes with “dome”), can sometimes include what’s known as an “aura.” An aura is actually a symptom of a focal seizure, which only affects one side of your brain.

When focal seizures don’t spread, an aura is the only effect of the seizure. When focal seizures do spread throughout your brain, an aura is more like a warning sign that a more severe seizure is about to happen.

Auras can also take many different forms. These include:

Different types of seizures have different kinds of symptoms, and describing the symptoms to a healthcare provider can help them diagnose and treat the kind of seizures you have. The two main types of seizures are generalized and focal.

The main types of generalized seizures are:

Formerly known as “grand mal” seizures (French for “great illness”), tonic-clonic seizures are usually the most recognizable. They happen in the following phases:

Formerly known as “petit mal” (French for “little illness”) seizures, these are most common in children. Absence seizures often look like daydreaming, “spacing out” or staring off into the distance (a “thousand-yard stare”). These seizures end quickly with no recovery period needed.

Absence seizures are short-lived but you can have dozens or even hundreds of times in a day. They’re easily confused for distraction or a sign of a learning disability.

Generalized seizures can happen in other ways that have similarities to those above:

Focal seizures affect a smaller area of your brain and stay in one hemisphere. These are also known as partial seizures, and auras — when they happen — come before these. Symptoms such as uncontrolled muscle movements may spread to different places on one side of your body, such as from one side of your face to the hand or foot on the same side.

Focal seizures include the following subtypes:

When a focal seizure spreads to the other side of your brain, it can turn into a generalized tonic-clonic seizure. If you’ve had a seizure in the past, or you know you have epilepsy, you should treat an aura like a warning sign. To protect yourself, you can do the following:

Seizures can happen for many different reasons. These include:

Children can have seizures for any of the above reasons. Fevers are one of the most common causes of childhood seizures. Other causes include:

No, seizures aren’t contagious. While you can spread conditions like infections that cause them, none will definitely cause a seizure. Also, some conditions that cause seizures are genetic (you can inherit them, or you can pass them to your children).

A healthcare provider, usually a neurologist, can diagnose a seizure based on symptoms you had and certain diagnostic tests. These tests may help confirm whether or not you had a seizure and — if you did — what might have caused it. Genetic tests can also help find inherited conditions that cause seizures (and sometimes even the most likely type of seizures you could have).

A key part of diagnosing seizures is finding if there’s a focal point — a specific area where your seizures start. Locating a focal point for the seizures can make a huge difference in treatment.

Possible tests with to help diagnose seizures include:

Providers might also recommend tests if they suspect injuries, side effects or complications from a seizure. Your healthcare provider is the best person to tell you (or someone you choose to make medical decisions for you) what kind of tests they recommend and why.

With provoked seizures, treating or curing the condition causing your seizures will usually make them stop. In cases where the underlying condition isn’t curable or treatable, healthcare providers may recommend medications to try to reduce how severe your seizures are and how often they happen medications.

Providers usually recommend against treating first-time unprovoked seizures. That’s because there’s no certainty that another will happen. An exception to that is if the person has a higher risk of having another seizure, or when a person has status epilepticus. Stopping status epilepticus is critical because it can lead to permanent brain damage or death. Healthcare providers can use your medical history and tests like EEG, CT scan or MRI scan to determine if you have a higher risk of having another seizure.

The treatments for seizures vary widely. That’s because the treatment for a provoked seizure depends almost entirely on the cause. The treatment for epilepsy-related seizures also depends on the type(s) of seizure you have, why they’re happening and which treatments work best.

Possible treatments for seizures due to epilepsy include one or more of the following:

The complications from seizure treatments vary widely, depending on the cause, type of seizure, type of treatment and more. Your healthcare provider is the best person to tell you what side effects or complications are most likely in your case. That's because they can give you specific information about your specific case.

You shouldn’t try to self-diagnose or treat a seizure. That’s because seizures are often a sign of very serious medical conditions that affect your brain. If you or a loved one have a first-time seizure, see a healthcare provider. Your healthcare provider can tell you what symptoms or effects to watch for that could mean you need medical care after a seizure.

If you're with someone who's having a seizure, there are several things you can do as part of seizure first aid. Some Dos and Don’ts include:

The time to recover from treatment depends on the types of seizures you have and the treatments you receive. Your healthcare provider can tell you what you should expect, including how long you’ll need to recover and when you should start to feel better.

Everyone is at risk for seizures, and they also happen unpredictably, so it’s not possible to completely prevent them. The best thing you can do is avoid possible causes to reduce the chances of having a seizure.

The best things you can do to reduce your risk of having a seizure include:

Fewer than half of people who have a single unprovoked seizure will have another. If a second seizure happens, healthcare providers usually recommend starting anti-seizure medications.

Medications can help prevent seizures or reduce how often they happen. However, it sometimes takes trying multiple medications (or combinations of them) to find one that works best.

In some cases, people have “refractory epilepsy,” which resists medications. For people with refractory epilepsy, surgery, ketogenic diet or an implantable device are the next options to consider.

For provoked seizures, the risk of having another depends on what caused the first seizure and if that cause was treatable or curable. If it was treatable or curable, your risk of having another seizure is low (unless you have a repeat of the circumstances that caused the first seizure).

Many people who had an unprovoked seizure will never have another for the rest of their lives. For those who do have a second seizure, epilepsy is a life-long condition because it’s not curable. However, it’s possible for this condition to go into remission and for seizures to stop happening.

For people who've had one or more seizures, the prognosis and outlook depend on several factors. These include:

In general, provoked seizures tend to have the best outlook if the underlying condition is treatable or curable. Provoked seizures with severe or recurring conditions are difficult to treat. It's also usually difficult to treat seizures and epilepsy that happen with congenital or inherited conditions.

The outlook for unprovoked seizures depends on the kinds of seizures, how often they happen, if medication helps them and more. In general, two-thirds of people with epilepsy can expect their seizures to be managed for a year or longer after trying one to two well-chosen and well-dosed anti-seizure medications. Your healthcare provider is the best person to tell you the outlook and what you can do to help yourself. They can tailor that information to your specific case and direct you to other providers and resources for additional help.

There is a small risk of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) for people with that condition. SUDEP happens for unknown reasons. Experts suspect it involves heart rhythm or breathing problems.

For people with managed (treated) epilepsy, the death rate each year is about 1 person out of every 1,000. For people with unmanaged (untreated) epilepsy, the death rate each year is about 1 out of every 150.

If you've had one seizure in the past, it's important to watch for signs of another. If you have a second seizure, seeing a healthcare provider as soon as possible is very important. Seizures cause changes in your brain that make it easier to have more seizures, so early diagnosis and treatment are key.

If a healthcare provider diagnoses you with epilepsy, you can help yourself by doing the following.

You should go to the emergency room if you have any event that makes you pass out, and you don't know what caused it. If you're alone and have what you think is a first-time seizure, you should call or see your healthcare provider right away.

Calling an ambulance after a seizure is often unnecessary if a person has epilepsy. However, even if they know why they had a seizure, they may have injuries that need medical attention.

If you’re with someone who has a seizure, you should keep in mind the following:

People with epilepsy can have children. While many anti-epilepsy medications aren't considered safe during pregnancy, most people with epilepsy can still have healthy children by working with a healthcare provider. Your healthcare provider is the best person to talk to guide you on this or refer you to a specialist.

A note from Cleveland Clinic

Seizures are not an uncommon neurological condition. About 11% of people will have a seizure at some point in their life, but most will have only one, and it's often for a specific reason. That means the one seizure won’t ever be a problem again. People who have more than one seizure without a specific underlying reason have epilepsy. While epilepsy is often a frightening condition, there are ways to treat it. With treatment, many people with epilepsy can live happy, fulfilling lives.

Last reviewed on 04/13/2022.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy